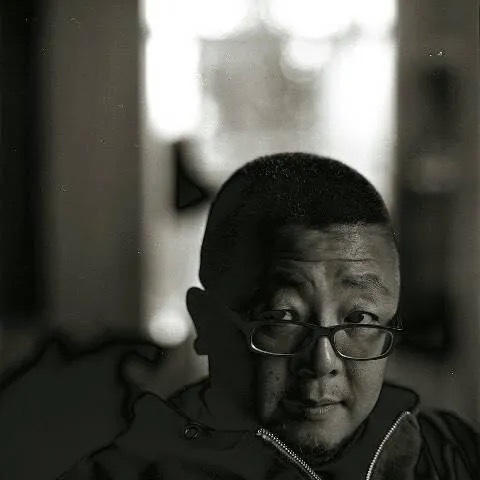

李一凡

2024.9.13-10.20

9.13 16:00 开幕

北京市朝阳区酒仙桥路2号798艺术区798东街 inner flow Gallery

全知失能

——AI数字绘画个展前的唠叨絮语

作为美院油画系唯一非绘画出身,也从不画画的教师,画不画、画什么、为什么画、怎么画从来不是我个人艺术创作的问题,它只存在于我的教学中和美学认知中。很多朋友都半开玩笑让我画点东西,想看看我的美学认知在二维平面上如何进行手工实践。疫情期间,杨述甚至给了一间绘画工作室让没法到处拍摄的我使用,我也曾动心,想看看美院附中毕业后再没摸过笔的自己,到底会在二维平面上实践出什么样的手工作品。但命运像给我开了个玩笑,因一些意外,连同杨述自己的工作室一起,整个艺术区没了。我一张画都还没画完的绘画生涯夭折了。

发现AI在某种程度上能生成我的绘画感受,有时甚至还有意外惊喜,非常偶然。起初我并没真拿它当回事,最多也就是想将它生成的图像作为某个展览的某种补充。但是,随着好奇心带来的深入,一种异样的美学上的断裂感,让我产生了强烈的探索实验的冲动。我想看看它究竟能做什么,它和我们习以为常的美学之间到底是种什么关系?我模模糊糊感觉到快速下沉的新技术对今天创作者与现实、图像、材料和观念的关系会造成极大的冲击,也许在限制成为日常的今天,我可以从这种美学的断裂中找到一种新的表达途径。

C_MEMORY003_1000*750H308_P1#LYF05032024

数字绘画、艺术微喷、铝合金框,100×75cm,2024

之后,我花了大量时间去研究、感受AI生成的艺术,我发现它在动态影像方面的技术还相当不成熟,但在二维图像作品生成方面已经出现了巨大的可能性,无论是摄影、绘画,还是在摄影和绘画之间的一些图像领域。它不需要任何手工技艺,只要你有图像认知能力,就可以实现各式各样的心中图像愿景。

我的AI创作是从记忆最深处开始的,因为是和机器工作,完全没有与人交往的杂念,整个过程非常恣意随性,那些曾经在心中驻留过的主观精神性图像,以及因为各种原因未曾实现的计划蓝图,甚至一些未来的工作计划,在我和AI的反复博弈中都渐渐显现出了它们各自的肉身轮廓。因为天性杂食,好奇心重,一度我生成的AI作品出现了十几个方向,随着实践探索的广泛深入,一些问题认知的权重开始在内心发生了变化。例如,艺术的平权问题,重构的伦理问题,失控的主动性和被动性与规训的关系问题,如何看待偶然性的陌生化与阐释,在受限制的时候如何使虚拟的自由转化成内在的自由,等等。

M_GARDEN003_1100-900H308_P1#LYF25082024

数字绘画、艺术微喷、木框,110×90cm,2024

AI作品生成实践期间,它巨大的可能性,尤其是对专业话语权力的解构给我带来了无限的喜悦,有点儿像当年第一次拿到DV开始拍自己的电影,从此心中再也没有电影厂、电视台一样。但,如何完全理解、定义和表现技术带来的偶然陌生化和主动选择的关系,如何更直接地表述当下的具身认知,这两点始终让我非常迷茫。有时会怀疑AI永远只能靠近心中的想法,无论如何与算法博弈,都无法直达,有点像霾中风景;而且直到整个展览创作过程结束,我也不能说清楚AI的图像生成机制,甚至也不能在使用中完全控制住它。为了解惑,也为了定义自己的作品和展览,我尝试着用chatgpt和各种伟大的思想家、艺术家聊天,希望从中得到一些启发或者明示,但收获非常有限,大多时候所谓全知并不全能。

ECHO_AI+A·C_3’18″V1#LYF19082024

AI影像,3’18”,2024

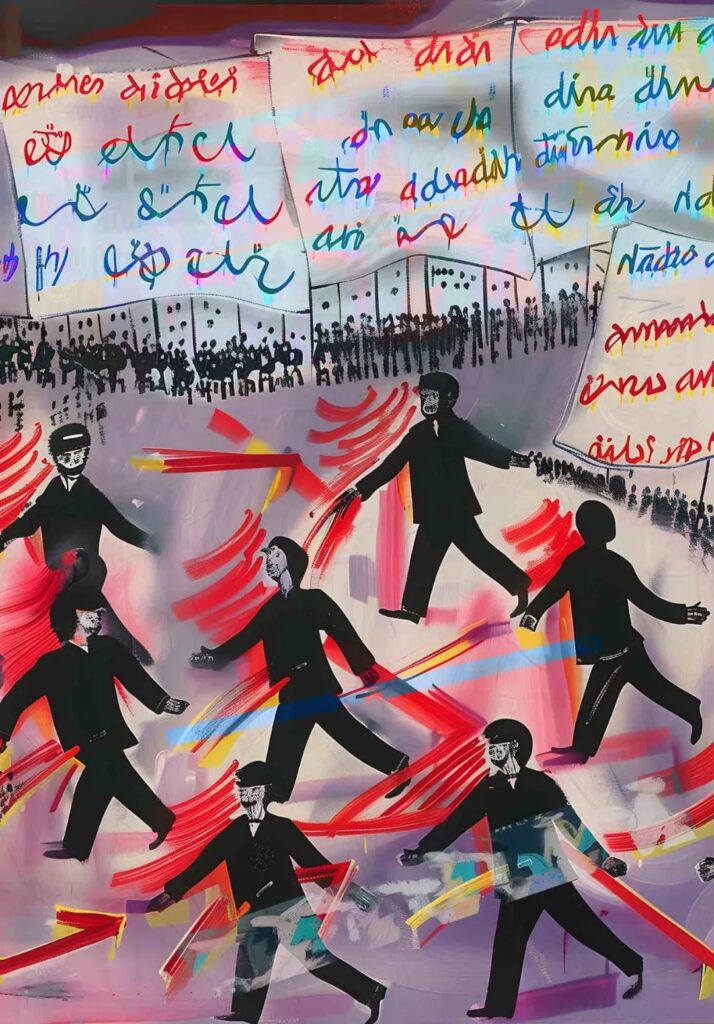

随着展期临近,我不得不确定所有展览作品,也包括我是否部分手工介入某些作品。我知道,在今天有相当多的艺术家在使用AI图形生成工具,然后再羞答答地把那些偶然陌生化的图形掩盖成手工产品,逃避AI带来的美学断裂,这其中甚至包括杰夫昆斯这样大名鼎鼎的艺术家的最新绘画作品。我从来不讨厌手工性,我甚至认为手工性是系统性权力中的BUG,它体现了个体与系统的断裂,非常宝贵。但是,在今天,一个以手工趣味至上的艺术环境里,对手工趣味的普遍膜拜已经让它快腐败成为系统性权力的一部分了。

S_POP006_760*530H308_P1#LYF09072024

数字绘画,艺术微喷,铝合金框,76×53cm,2024

放弃二维平面表达的手工性,甚至,像安迪沃霍尔那样用丝网版复制也必须放弃。我的困惑从来没有像这次做展览这么多,放弃手工性几乎是我唯一想清楚的问题,也是我在整个创作过程中体会到的两个最大的美学断裂之一(另一个是偶然的陌生化)。我知道AI生成的艺术确实带来了一种疏离感和断裂,但我也知道这不仅仅是技术带来的挑战,更是逃离习惯性认知,发现新的表达方式,新的观看方式,在技术主导的世界中重新审视自己的位置,坦然面对技术的荒谬性、以及这种荒谬性带来的生存处境,重新发现和定义自我主体性和存在的机会。事实上,最近两年我已经发现自己对许多问题的认知明显不足,虽然我依然和社会保持着相当强度的互动,但我却经常感到自己处在一种失语状态。这个展览原先我想起名「犹在镜中」,指的就是除了保持对外部的发现,也必须寻找到合适的工具反思自己的认知能力。

另外,在我决定完全放弃整个展览的手工性之前,我还重新思考了一遍十几年前与鲍栋的那场争论中,我首次使用“肉身经验”这个词当时究竟指的是什么。它肯定不是指一种趣味主义的肉身修行,不是身体对材料的把玩,也不是某种身体卖惨的表演,或者仅仅只是如何面对个人的深渊。它强调的是对社会的具身认知,是一个人如何理解个人经验的具体性、偶然性与社会共性之间的冲突。

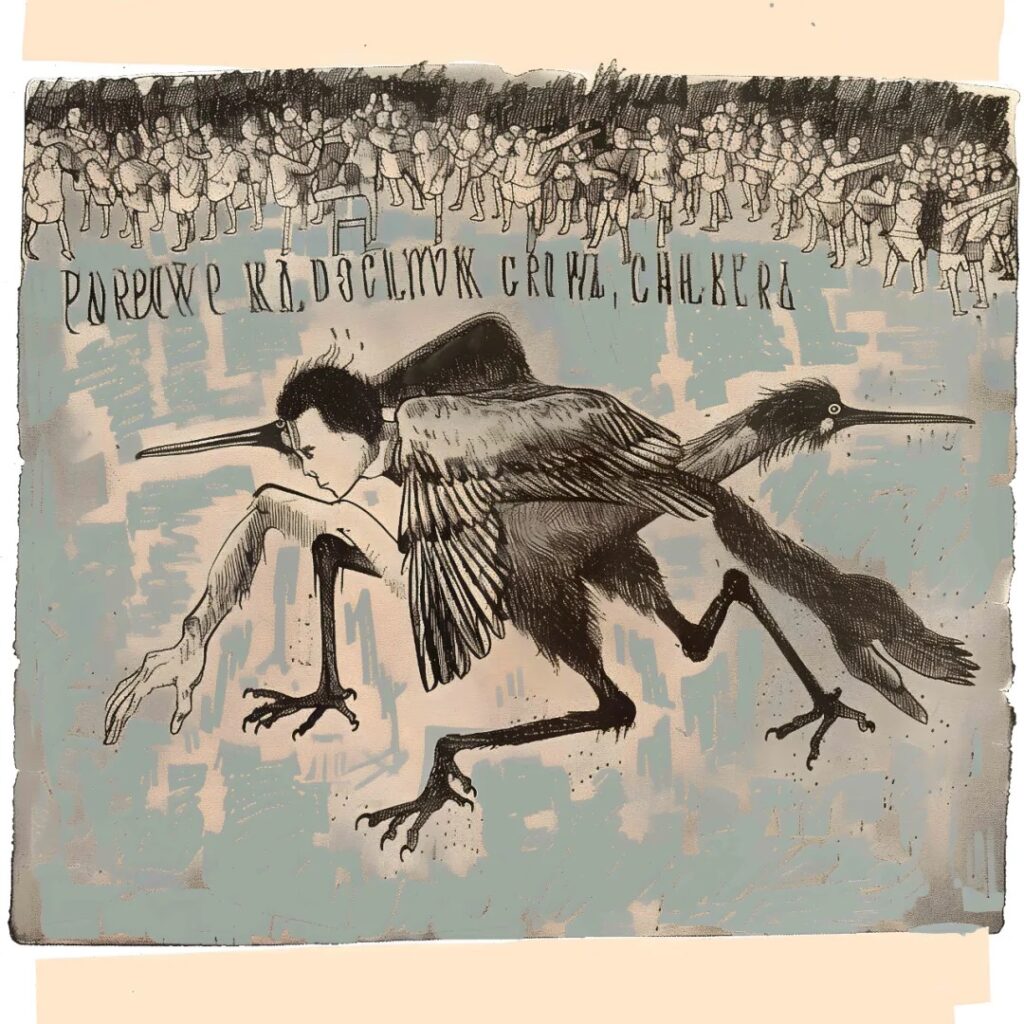

K_BRID006_500*500H308_P1#LYF09052024

数字绘画,艺术微喷,木框,50×50cm,2024

今年三月,为了准备这个展览,按惯性我去了东莞石排,本打算和拍流水线爱情短视频的工人混混,看能拍出些什么有意思的东西。结果我被那些村里作坊般小工厂的全自动无人流水线和智能机械臂震惊到了,尤其是在东莞东城的机器人工程师培训学校,看到第二百几十期工程师班毕业合照的时候。我无法想象短短三、四年间究竟发生了什么,使技术下沉如此之快。虽然2010年前后,我在沃尔夫斯堡花12欧元参观过大众汽车的工业4.0无人工厂,知道这个曾经7、8万工人的工厂,一个工班只需要280名工作人员了,但当时觉得那不过是一场与我无关的表演,离我的现实还遥远得很。

望着那些找不到工作的前杀马特们四处游荡,在石排的“名流”发廊听理发师小天讲,他们现在“洗心革面”想找工厂都很艰难。即使进了厂,这两年厂里为了和自动化无人流水线竞争,开的都是“飞机拉线”,没几个人能长时间扛住时,又突然接到深圳的建筑师朋友打来的电话,说AI让他失业了。

计划中的广东之行突然凌乱,原先打算的展览想法更是完全失序。万没想到迅速下沉的技术进步带来的社会断裂如此迅猛,令人难以招架。更可怕的是当我细思我们每天口中的那些经典理论和伟大实践样本,发现它们几乎都停留在2000年代之前的语境里,面对我们今天的处境它们共同显现的是一种失能状态。

S_POP017_760*530H308_P1#LYF25072024

数字绘画、艺术微喷、铝合金框,760×530,2024

这个展览对于我更像经历了一场狼狈之后的重启,它带给我发现新的认知方法和工作方法的可能性,让我喜悦。但是,我也清楚地知道,虽然每次工具的发明都带来人的感官和功能的延伸,也带来个人与社会的断裂,AI这次却相当不一样,因为它延伸的是人的想象力和表达想象力的手段,这次断裂最终会带来人的解放还是更大的禁锢我完全不能判断。

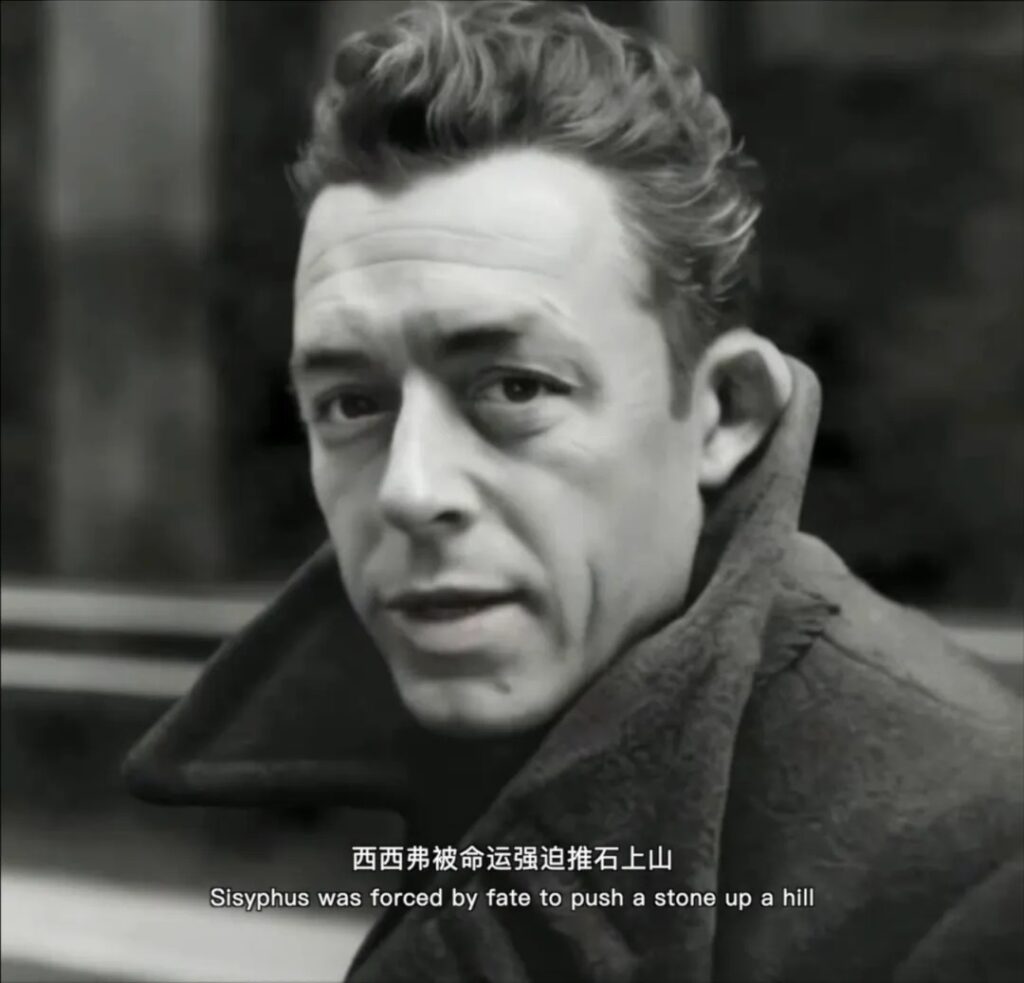

从某种意义上讲人工智能的到来和现代性的到来一样,不是你喜不喜欢它的问题,它来都来了,而且还将无处不在。我特别喜欢《鼠疫》中,奥兰城居民的态度:面对一种无法理解且不可抗拒的东西,只有积极面对,坦然接受任何结果,因为面对问题本身就是意义。

李一凡1966年出生于湖北武汉,1991年毕业于北京中央戏剧学院。 现工作生活于重庆,美院油画系教师。

艺术项目:《一个人的社会》、《临时艺术社区》、《六环比五环多一环》和《外省青年》等的主要发起人之一。纪录片:《淹没》、《乡村档案:龙王村2006影像文件》获得包括柏林电影节青年论坛沃尔夫冈·斯道特奖、法国真实电影节国际多媒体作者联合奖、日本山形国际纪录片电影节弗拉哈迪奖、香港国际电影节纪录片人道奖在内的数项国际性大奖,以及荷兰IDFA Jan Vrijman Fund电影基金奖和瑞士Vision sud est Fund电影基金奖。《杀马特,我爱你》在国内外文化界引起重大反响。

个展:2008年北京《微观叙事:档案》、2016年重庆《抵抗幻觉——日常生活的仪式》以及2019年广东《意外的光芒》等,较全面的体现了他在中国社会的现状下,用现实本身的超越性去创造新的美学的艺术思想。

2024.9.13-10.20

THE JOKE OF OMNISCIENCE

As the only teacher in the Oil Painting Department of the Academy of Fine Arts who didn’t come from a painting background and never paints, questions like whether to paint, what to paint, why to paint, and how to paint have never been part of my personal artistic creation. These questions only exist in my teaching and aesthetic understanding. Many friends jokingly encouraged me to paint something, eager to see how my aesthetic understanding would translate into a two-dimensional, handmade creation. During the COVID-19, Yang Shu even offered me a painting studio to use when I couldn’t travel for filming. I was tempted to see what I could create in two dimensions after not having touched a brush since graduating from the Academy’s secondary school. But as fate would have it, an unexpected event wiped out the entire art district, including Yang Shu’s studio, and my barely-begun painting career was cut short.

I discovered that AI could, in a way, generate my painting sentiments, sometimes even with surprising results. At first, I didn’t take it seriously, merely considering the generated images as a supplement for some exhibitions. However, as curiosity drove me further, a strange aesthetic rupture sparked a strong desire to experiment. I wanted to see what AI could do and what relationship it had with the aesthetics we are so accustomed to. I vaguely sensed that this rapidly advancing technology would significantly impact the relationship between creators and reality, images, materials, and ideas. Perhaps, in a time when restrictions have become commonplace, I could find a new way of expression through this aesthetic rupture.

Subsequently, I spent a great deal of time studying and experiencing AI-generated art. I found that while its dynamic video capabilities were still quite immature, it had already shown tremendous potential in generating two-dimensional images, whether in photography, painting, or the space between the two. It doesn’t require any manual skills; all you need is an understanding of images, and you can bring various visions to life.

My AI creations began from the deepest recesses of my memory. Since I was working with a machine, free from the distractions of human interaction, the process was completely spontaneous. The subjective, spiritual images that had lingered in my mind, the unrealized plans for various reasons, and even some future work plans gradually took shape as I interacted with the AI. My natural curiosity led me in many directions, and at one point, my AI-generated works followed over a dozen different paths. As my exploration deepened, the weight of certain issues began to shift within me—for example, questions of artistic equality, the ethics of reconstruction, the relationship between control and passivity, how to view the alienation of chance and interpretation, and how to transform virtual freedom into inner freedom under constraints.

During my practice of AI generation, its immense possibilities—especially its deconstruction of professional authority—brought me boundless joy. It was somewhat like when I first got my hands on a DV camera and started making my own films, rendering film studios and television stations irrelevant. Yet, I remained confused about how to fully understand, define, and express the relationship between the alienation brought by technology and the conscious choices we make, and how to more directly express embodied cognition in the present moment. Sometimes, I wondered whether AI would ever be able to truly realize my inner visions, no matter how much I engaged in a back-and-forth with its algorithms. It was like trying to see a landscape through fog. By the time the exhibition creation process ended, I still couldn’t fully articulate AI’s image-generation mechanism, nor could I completely control it. To seek answers and define my works and the exhibition, I tried chatting with ChatGPT and various great thinkers and artists, hoping for inspiration or enlightenment, but the results were very limited. All-knowing does not mean all-capable.

As the exhibition approached, I had to finalize all the works, including whether or not to manually intervene in some pieces. I was aware that today many artists use AI image generation tools and then subtly disguise those alien, chance-produced images as handmade products, avoiding the aesthetic rupture AI brings—this even includes famous artists like Jeff Koons. I’ve never been against manual craftsmanship; I believe it’s a BUG in systemic power, representing a rupture between the individual and the system, which is incredibly valuable. However, in today’s art world, where there’s a supreme reverence for craftsmanship, this obsession has almost become part of systemic power itself.

Abandoning manual craftsmanship in two-dimensional expression, even using silk-screen printing like Andy Warhol, was something I had to give up. I’ve never been more conflicted in creating an exhibition; giving up craftsmanship was the only issue I was clear about. It also led me to experience two of the greatest aesthetic ruptures in the process—one being the alienation of chance. I knew that AI-generated art brought a sense of detachment and rupture, but I also knew that it wasn’t just a challenge brought by technology. It was an escape from habitual thinking, a discovery of new ways to express and view, a reevaluation of one’s position in a tech-dominated world, and a chance to confront the absurdity of technology and the existential state it imposes, rediscovering and redefining one’s subjectivity and existence. In fact, in recent years, I’ve realized that my understanding of many issues is increasingly inadequate. Though I still maintain strong social interactions, I often feel a sense of speechlessness. The exhibition was originally titled Still in the Mirror, referring to the need to not only continue discovering the external but also to find the right tools to reflect on one’s cognitive abilities.

Before deciding to completely abandon craftsmanship in this exhibition, I revisited the debate I had with Bao Dong more than a decade ago, where I first used the term “embodied experience.” What did it mean then? It certainly wasn’t about a fetishistic pursuit of bodily discipline, nor about the body playing with materials, nor about some kind of performative display of bodily suffering or just facing personal despair. It emphasized embodied cognition of society—how a person understands the conflict between the specificity and contingency of personal experience and social commonality.

In March of this year, while preparing for the exhibition, I went to Shipaizhen in Dongguan, as was my habit, intending to mingle with workers filming short videos about assembly line romances and see if I could capture something interesting. Instead, I was shocked by the fully automated, unmanned assembly lines and robotic arms in the village-like small factories. I was especially struck at the robotics engineer training school in Dongguan’s Dongcheng, where I saw the graduation photos of the 200+ classes. I couldn’t imagine what had happened in just three or four years for technology to advance so quickly. While in the early 2010s, I had paid 12 euros to tour Volkswagen’s Industry 4.0 unmanned factory in Wolfsburg, and I knew that a factory that once employed 70,000 to 80,000 workers now only required 280 workers per shift, it had seemed like a distant show that had nothing to do with my reality.

Seeing former “Shamate” youth aimlessly wandering around after losing their jobs, hearing a hairdresser in Shipaizhen’s “Celebrity” salon talk about how difficult it was to find factory work now, and learning that even if they got hired, most couldn’t handle the long hours competing with automated lines, I suddenly received a call from a friend in Shenzhen, an architect, saying that AI had put him out of a job.

The planned trip to Guangdong quickly fell into disarray, and my initial exhibition ideas completely collapsed. I never expected the social rupture caused by rapidly advancing technology to be so swift and overwhelming. Worse, as I reflected on the classic theories and great practical examples we discuss daily, I realized that most of them are still stuck in the context of the early 2000s, rendering them impotent in addressing today’s realities.

LI YIFAN

Born in Wuhan, Hubei in 1966, graduated from the Central Academy of Drama in 1991, now teaches oil painting at arts Institute, currently lives in Chongqing.

He is also one of the main initiators of the art projects All Individual As the Society, Tentative Art Community, Between the 5th and 6th Ring Road in Beijing, and Youth in Foreign Provinces.

His documentaries Before the Flood (2005) and Chronicle of Longwang: A Year in the Life of a Chinese Village (2008) have won several international awards, such as Wolfgang Staudte Award at the Berlin International Film Festival, Prix international de la Scam at Cinéma du Réel, The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize at Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival,Documentary Competition Prize at Hong Kong International Film Festival, also includes IDFA Jan Vrijman Fund and Vision sud est Fund. We were Smart has caused a great response in the cultural circles both at China and abroad.